News and Updates

The latest from the Deccan Heritage Foundation

Browse our newsletters, and stay current on the latest announcements regarding our projects, publications, and events.

Discover our latest restoration milestones across Hyderabad, Mysuru and Sudi.

The West Block Corridor at our ongoing restoration project, Jayalakshmi Vilas Mansion and Folklore Museum, Mysuru

Our latest newsletter brings exciting news from the DHF–a new restoration project in Hyderabad that builds on the DHF’s mission to foster education and adaptive re-use of historic spaces. We also take you behind the scenes at the conservation lab at Jayalakshmi Vilas Mansion & Museum in Mysuru and share updates from Sudi, where our team continues work on a 1000-year-old stepwell.

A New Project at The British Residency, Hyderabad

The Physics Block at Osmania University Women’s College (Telangana Mahila Vishwavidyalayam)

Following the restoration of the Rang Mahal at the former British Residency in Hyderabad, the DHF is now undertaking the partial restoration of the Physics Block and a historic stepwell within the same complex, now home to the Veeranari Chakali Ilamma Women’s University (VCIWU). Work is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

This project is supported by The Rainwater Project.

Inside the Conservation Lab at Jayalakshmi Vilas Mansion & Museum, Mysuru

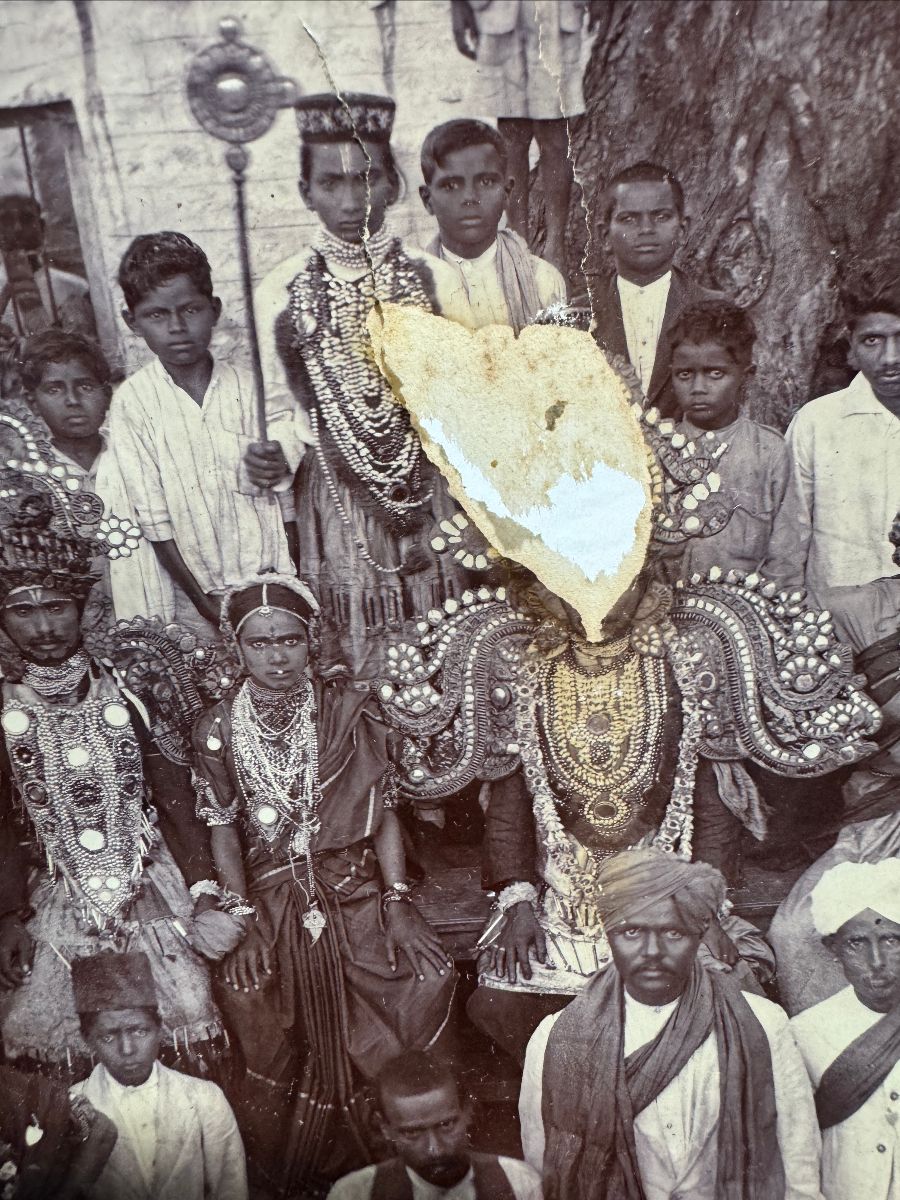

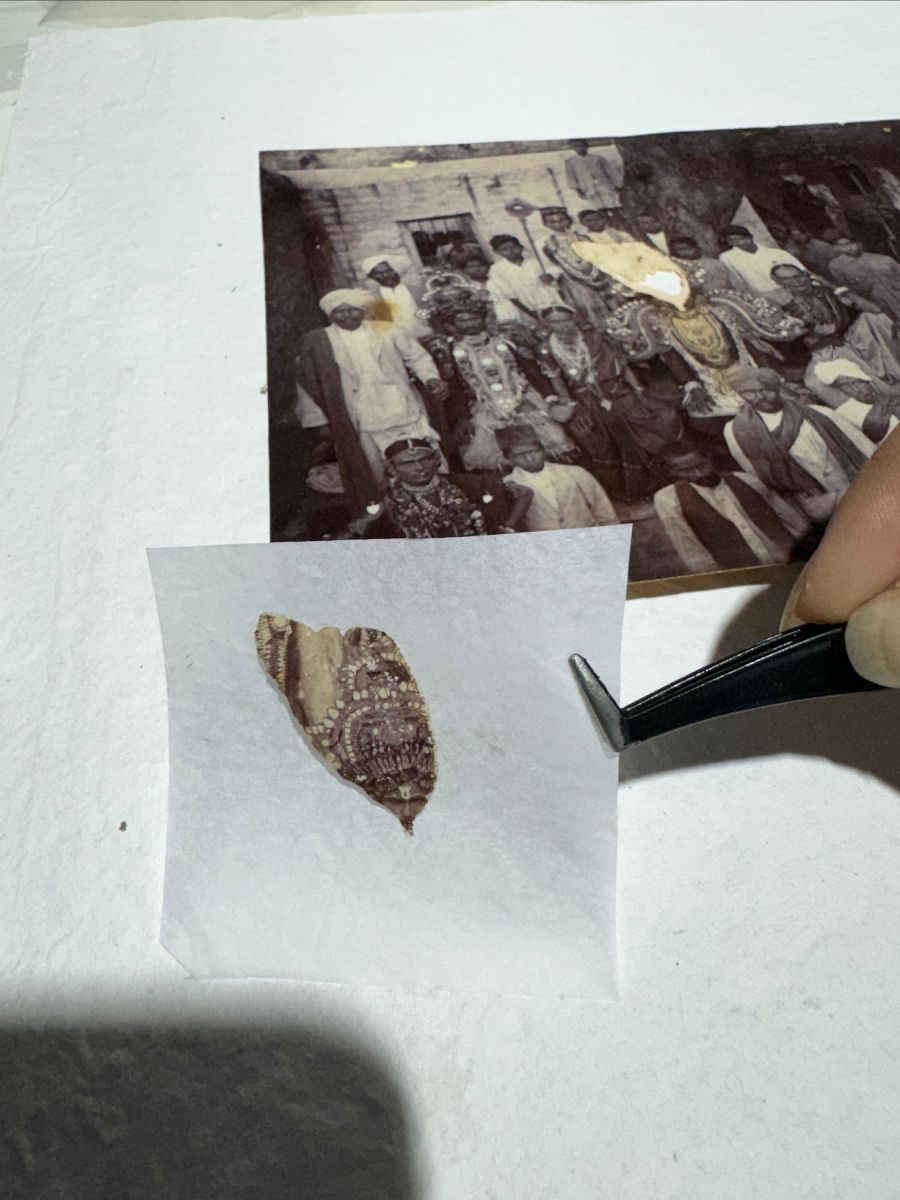

The conservation team treating an old photograph from the collection of Jayalakshmi Vilas Mansion & Museum, Mysuru, Karnataka

The team at Jayalakshmi Vilas Mansion is hard at work, conserving the museum’s historic collection, which includes remarkable artefacts of folk, ritual, and everyday life in Karnataka. With generous support from the Aikyam Foundation, we are also in the process of establishing a formal Department of Restoration and Photography, along with the “Manisha Dhawan Learning Center for Conservation”. JVM’s conservation lab will be a regional hub for pioneering research and training, supporting not only the restoration of the museum’s vast collection, but also conservation efforts throughout the Deccan and across India.

Step inside the lab and see what the JVM team is currently working on.

Photographs

Historic photographs are being preserved through careful cleaning, adhesive removal, and surface stabilisation to ensure their long-term safety. Each image offers a glimpse into the lives and moments of history, reminding us that conservation is not just about preserving objects, but also the stories they carry.

Ganjifa Cards

With the help of expert consultants, the team is documenting and conserving a collection of Ganjifa cards—traditionally hand-painted playing cards known for their vibrant colours, circular form, and intricately detailed figures and motifs. Widely popular during Mughal India, Ganjifa is believed to have originated in Persia.

Bhuta Sculptures

Leather Puppets

This fragile set of twenty-six leather puppets, once used to tell stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, is being carefully cleaned, flattened, and stabilised by our team. Typically made of goat or deer skin and painted in vivid colours, they bring to life Karnataka’s rich storytelling tradition.

The JVM project is supported by the Harish & Bina Shah Foundation (HBSF), the US Consulate General in Chennai, through the Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation (AFCP), and the Aikyam Foundation.

Project Updates from Sudi

Soil removal and scaffolding at the Nagakunda Stepwell, Sudi

At the Nagakunda stepwell in Sudi, preparations are in full swing as we ready the site for the next stage of restoration. Lime concrete has been laid on parts of the stepwell terrace, and deteriorated plaster is being carefully removed. Work is also progressing on dismantling structurally unstable walls and surfaces, while scaffolding and temporary supports have been put in place. With each step, the team moves closer to reviving this beautiful water system and its sacred landscape. More information about the project can be found here.

This project is supported by Mrs. Rajashree Pinnamaneni, in memory of Dr. Subba Rao Devineni.

We look forward to bringing you more news, project updates and insights from the sprawling Deccan region. To support the DHF’s restoration and conservation efforts, consider making a donation by clicking the button below.

Previous Newsletters and updates